Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Duration 8:06

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Plummer XD, Liang A

Clinical Case Applicability: urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse

Learning Objectives:

1. Describe the normal anatomy of the pelvic floor

2. Understand the pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse (POP)

3. Understand the different management options for POP

Clinical Presentation: A sensation of bulging in the vagina that can be accompanied by urinary/fecal incontinence, incomplete bladder emptying, constipation, dyspareunia; NOT typically painful

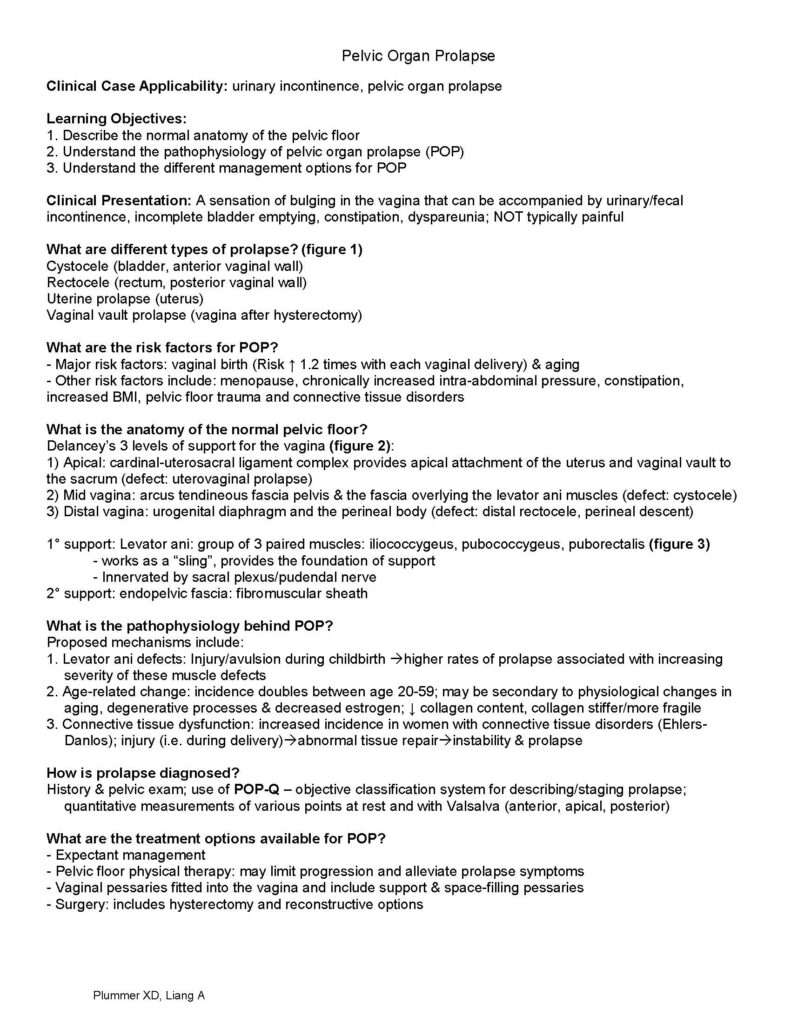

What are different types of prolapse? (figure 1)

Cystocele (bladder, anterior vaginal wall)

Rectocele (rectum, posterior vaginal wall)

Uterine prolapse (uterus)

Vaginal vault prolapse (vagina after hysterectomy)

What are the risk factors for POP?

– Major risk factors: vaginal birth (Risk ↑ 1.2 times with each vaginal delivery) & aging

– Other risk factors include: menopause, chronically increased intra-abdominal pressure, constipation, increased BMI, pelvic floor trauma and connective tissue disorders

What is the anatomy of the normal pelvic floor?

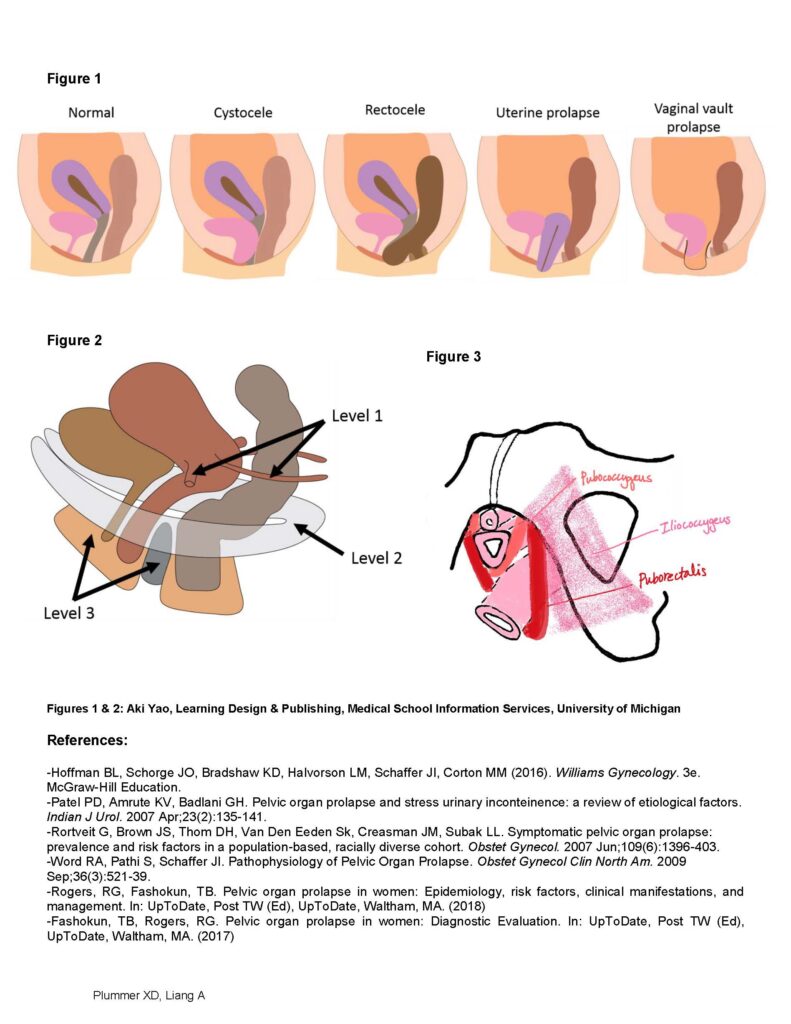

Delancey’s 3 levels of support for the vagina (figure 2):

1) Apical: cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex provides apical attachment of the uterus and vaginal vault to the sacrum (defect: uterovaginal prolapse)

2) Mid vagina: arcus tendineous fascia pelvis & the fascia overlying the levator ani muscles (defect: cystocele)

3) Distal vagina: urogenital diaphragm and the perineal body (defect: distal rectocele, perineal descent)

1° support: Levator ani: group of 3 paired muscles: iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, puborectalis (figure 3)

– works as a “sling”, provides the foundation of support

– Innervated by sacral plexus/pudendal nerve

2° support: endopelvic fascia: fibromuscular sheath

What is the pathophysiology behind POP?

Proposed mechanisms include:

1. Levator ani defects: Injury/avulsion during childbirth higher rates of prolapse associated with increasing severity of these muscle defects

2. Age-related change: incidence doubles between age 20-59; may be secondary to physiological changes in aging, degenerative processes & decreased estrogen; ↓ collagen content, collagen stiffer/more fragile

3. Connective tissue dysfunction: increased incidence in women with connective tissue disorders (Ehlers-Danlos); injury (i.e. during delivery)abnormal tissue repairinstability & prolapse

How is prolapse diagnosed?

History & pelvic exam; use of POP-Q – objective classification system for describing/staging prolapse; quantitative measurements of various points at rest and with Valsalva (anterior, apical, posterior)

What are the treatment options available for POP?

– Expectant management

– Pelvic floor physical therapy: may limit progression and alleviate prolapse symptoms

– Vaginal pessaries fitted into the vagina and include support & space-filling pessaries

– Surgery: includes hysterectomy and reconstructive options Plummer XD, Liang A

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figures 1 & 2: Aki Yao, Learning Design & Publishing, Medical School Information Services, University of Michigan

References:

-Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Bradshaw KD, Halvorson LM, Schaffer JI, Corton MM (2016). Williams Gynecology. 3e. McGraw-Hill Education.

-Patel PD, Amrute KV, Badlani GH. Pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary inconteinence: a review of etiological factors. Indian J Urol. 2007 Apr;23(2):135-141.

-Rortveit G, Brown JS, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden Sk, Creasman JM, Subak LL. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: prevalence and risk factors in a population-based, racially diverse cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jun;109(6):1396-403.

-Word RA, Pathi S, Schaffer JI. Pathophysiology of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009 Sep;36(3):521-39.

-Rogers, RG, Fashokun, TB. Pelvic organ prolapse in women: Epidemiology, risk factors, clinical manifestations, and management. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (2018)

-Fashokun, TB, Rogers, RG. Pelvic organ prolapse in women: Diagnostic Evaluation. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (2017)